Direct-to-consumer drug marketing has become an important part of the pharmaceutical industry. We see ads on TV, in magazines and newspapers, on webpages, and we hear them on the radio. Mary Ebeling has recently written about how companies use checklists to present symptoms. She finds that the checklist has a particular authority with consumers that makes it a useful marketing tool. See her article “‘Get with the Program!’: Pharamceutical Marketing, Symptom Checklists and Self-Diagnosis” in Social Science & Medicine (it is behind a paywall, so read the NY Times article based on it: “Have These Symptoms? Buy This Drug”).

Direct-to-consumer marketing and disease mongering is nothing new. Patent medicine manufacturers became rich doing much the same thing in the 19th and early 20th century. See my earlier post: “Marketing Drugs, Then and Now.” But even the patent medicine companies, like Philadelphia’s own Dr. Jayne’s Family Medicines) or Wright’s Indian Vegetable Pills or J.C. Ayer & Co were simply reusing techniques that had been deployed successfully for centuries. This post uncovers an earlier episode, in the late 17th century, when purveyors of cure-alls advertised their wares to an eager public. This case study reveals some of the enduring techniques makers of such medicines used to sell their concoctions—such as listing of symptoms for self diagnosis, invoking personal testimony, discrediting their competitors, and offering free samples. It also reveals the financial gains that awaited the successful marketing campaign.

Sometime around 1680 an anonymous flier advertised “Pilulæ Antiscrobuticæ,” pills that promised to cure “that Epidemical Disease the Scurvy.” Just in case the reader was unsure what scurvy was, the pamphlet recounted telling symptoms, “for the Instruction of the Ignorant:”

Putrefaction of the Gums; rotten, black, and loose Teeth; stinking Breath; laziness and dulness of the Limbs, and the whole Body; giddiness of the head; sudden Flushings, heat and redness in the Face; some have risings on their Body as if stung with Bugs; spots in the Legs and Thighs, of red, black, purple, or blue colour; others have an itching in some or all parts of the Body; a shortness of Breath, red Gravel in the Urine like Brick-dust, strange Pains and Aches in several parts of the Body; Fluxes of the Belly, Dysneteries, swellings and breakings out in the Body….

The pilulæ antiscorbuticæ, the pamphlet promised, cured all manner of ailment. In addition to scurvy, they opened obstructions of the womb, liver, spleen, and stomach. They cured diseases of the head such as vertigo, swimming of the head, palsy, coma, lethargy, apoplexy, dropsy, as well as “hypocondriack vapours.” A box of 18 of these wonder pills could be purchased for 1 shilling and 6 pennies from “Mr. Hallifax Ironmonger, next door to the Cross Inn in Oxford,” a bookseller’s in Coventry, a coffeehouse in Buckingham Court, a barber’s in Ship-Ally in Well-Close, among other places.

The pilulæ antiscorbuticæ were not the first medicines marketed directly to a public and were not the last. In 1678, another anonymous flier advertised the Catholick of Universal Pill, which cured “the Scurvy, Dropsy, Jaundise, Leprosy, Kings-evil, Green Sickness, or any other Chronick Distemper whatsoever, which my printed Books which are given out with each Box of Pils will inform you of the Names, and Places of Abode of several Persons that have been cured by them.” Here we see one of the key pieces of direct marketing, the testimonial. The flier promises to provide names and addresses of people who have been cured and can testify to the efficacy of the Catholick Universal Pill.

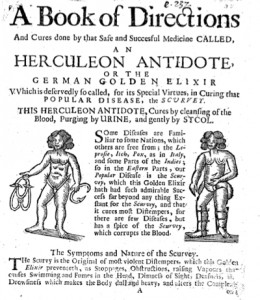

Apparently scurvy was suddenly quite a problem in England, or at least quite a marketing opportunity. In one pamphlet Humphrey Nendick warned his readers that “Some Diseases are Familiar to some Nations … our Popular Disease is the Scurvey.” Nendick had a vested interest in worrying his reader. He was himself a proprietor of the “Herculeon Antidote or the German Golden Elixir.”

Nendick wasn’t alone. In the 1670s and 1680s a number similar medicines were suddenly available, all promising to cure scurvy, dropsy, and a range of other “chronic distempers,” and all competing for the public’s money. Some of them include:

- Anthony Daffy Daffy’s original elixir salutis, vindicated against all counterfeits, &c. or, An advertisement by mee, Anthony Daffy, of London, citizen and student in physick by way of vindication of my famous and generally approved cordial drink, (called elixir salutis) from the notoriously false suggestions of one Tho. Witherden of Bear-steed in the county of Kent… (1675)

- Thomas Witherden, Elixir salutis; or the great preservative of health called by some, the never-failing cordial of the world. : Being most pleasant and safe for all ages, sexes, and constitutions … / Prepared by me, Tho. Witherden (1679)

- Bowcher, Bowcher’s famous and most highly approved spirits of scurvy-grass, both golden and plain, being the best that ever were made (1680?)

- Joseph Sabbarton, To make the true compound Elixir of scurvy-grass, and horse-radish (1680)

- Valentin Moellenbrock, The curiosities of scurvy-grass (1689)

The market was clearly competitive. One maker, a Robert Bateman, waged something of a struggle with other purveyors of cure-alls, especially Charles Blagrave and Sieur de Vernates:

- Robert Bateman, Batemans hue-and-cry after the pretended Sieur de Vernantes, and his counterfeit spirit of scurvey-grass (1680)

- Robert Bateman, A gentle dose for the fool turn’d physician. Or a brief reply to Blagraves ravings (1680)

- Robert Bateman, The true spirit of scurvey-grass with its vertues (1680)

- Robert Bateman, Eminent cures lately perform’d in several diseases, by Batemans; Spirits of scurvey-grass (1681)

- Charles Blagrave, Blagrave’s advertisement for his spirits of scurvey-grass (1680)

- Charles Blagrave, Directions for the golden purging spirit of scurvey-grass (1680)

- Charles Blagrave, Doctor Blagrave’s excellent and highly approved spirits of scurvey-grass, both plain and the golden purging, faithfully prepared according to his own directions (1680)

- Anonymous, A recommendation of that high and most noble medicine, the essential spirit of scurvey-grass compound; the invention and preparation of the sieur de vernantes (1680?)

The key ingredient in these various remedies was “scurvy grass,” The English herbalist Nicholas Culpepper offered a robust description of scurvy grass in his The Complete Herbal (1653). He identified various forms—common, Dutch, ivy-leaved, Greenland, sea, and horse-radish—and described their virtues. Scurvy grasses were “herbs of Jupiter” and possessed “a considerable degree of acrimony.” Dutch scurvy grass was, apparently, more effective in curing scurvy and cleansed “the blood, liver, and spleen … and opens obstructions, evacuating cold, clammy and phlegmatic humours both from the liver and the spleen, and bringing the body to a more lively colour.”

These handbills, fliers, and pamphlets reveal some common techniques for marketing medicines to a 17th-century public. First, present a full list of possible symptoms: stoppages, obstructions, fumes in the head, drowsiness, inflammation, worms, stinking breath, black teeth, feebleness in the limbs, running aches, scabs, barrenness, wandering pains, itchings, gravel in the kidneys, melancholiness, wind-cholick, hypochondriack, and the lists go on. These lists alternate seamlessly between specific names of ailments such as “the King’s-Evil” with general symptoms like “inflammation.” Nearly any discomfort will fall under one of the symptoms.

Along with symptoms these pamphlets often included testimonials from regular people who had been cured or who had used the medicine to cure a member of the family. This is the 17th-century version of “Real Guys. Real Stories” in which regular people recount their efforts to regain their health:

Mr Rider Gunlockmaker near the Cross Guns in Goodmans Fields, cured his Man of a Scurvy, and Gross Humours, and Boiles in the Flesh. Mrs. Warren her Grand daughter was cured of a Scorbutical Humour that fell upon her Eyes, and took away her Sight, is now perfectly cured.

Other testimonials guaranteed the product’s effectiveness for each of the many symptoms it was reported to cure, even when other cures had implicitly or explicitly not worked:

2. Children of Mrs. Pulfords aforesaid, were cured, one of them was cured of the Griping of the Guts and a Looseness in the Small Pox; and the other of a violent Fever in the Small Pox, and were judged past recovery but are now in perfect health.

Clearly, testimony was already a standard marketing tool.

The scurvy-grass market was clearly crowded. Most pamphlets distinguish their medicines from competitors, sometimes naming their competition and other times simply describing the inferior products. Don’t be lured in by cheap imitations, “this true spirit of Scurvey-Grass, which is truly prepared without Adulteration, performs all that those unwholsom Drinks pretend to, and you will find one drop more beneficial to your Health than a whole gallon of their crude undigested Liquors.” In an effort to reassure the buyer that a particular medicine was of the highest quality, pamphlets often attributed to other scurvy-grass remedies a range of side effects. At the same time, they assure the reader that no such ill effects attended to their own medicine: “The Golden Purging Spirit, is of that excellent quality that, though a very small quantity will give a considerable Purge yet it does it so pleasantly that it leaves no manner of Offence to the Stomach.” Robert Bateman carried on a protracted contest with various other makers, including Blagrave, and Sieur de Vernantes, and unnamed other competitors.

In case the testimonials and the efforts to discredit competitors failed to convince the public, many purveyors of such remedies offered free advice and samples. They invited readers to come for free consultations: “I am to be spoken with at my House in Alley Street overagainst Harrow Alley … at the Sign of the Good Samaritan, from 8 in the morning to 12 and from 2 to 8.” They also offered free samples: “And, for Satisfaction, any Person may smell it or taste it at the Author’s House, for nothing, as above directed.”

Scurvy-Grass remedies were a business, so each flier ends by telling the reader how much these elixirs and wonder pills cost and where to buy them. “This Elixir and Pills [Herculeon Antidote] are sold by the Persons following in the Long Half Pint Bottles Price 2s. 6d, and the lesser bottle 1s. 6d. Sealed with my cot of arms, the Flying Swan and Crown.” Bowcher’s Golden and Plain Spirits could be had for 1s from “Mr. Moor Stationer, Mr. Kelo Haberdasher of Hats, Mrs. Garnet Milliner, Mr. Heath at the German-Bird-House, … at the Holy Lamb and Brandy Shot in Fetter-lane” and various other places. Booksellers commonly sold scurvy-grass medicines. Many of these medicines cost between 1s. 6d. and 2s, which seems like a reasonably expensive purchase.

Although the scurvy epidemic seems to have faded fairly quickly, probably replaced by another epidemic—advertisements for scurvy-grass remedies fall off dramatically after 1700—this episode wasn’t some historical aberration. Scurvy-grass wasn’t the first time physicians, quacks, herbalists, apothecaries, or entrepreneurs tried to profit from the public’s fears about a particular disease. Previously, nearly every time plague broke out in a city a flood of pamphlets and guides appeared offering guidelines for people on how to avoid or treat the plague. Since then an entire industry based on selling home-remedies directly to people has come and gone—the patent medicine or proprietary medicine industry. And today we see yet further iterations of these techniques: pharmaceutical companies spend more than $2 billion marketing their wares directly to consumers; “complementary and alternative medicine” spend untold millions on similar marketing strategies. However much the science and medicine might change, the techniques for selling health seem to survive those changes.

[Reposted at PACHS.]

8 replies on “A Scurvy Epidemic in 17th-Century England”

[…] Darin Hayton of the PACHSmörgåsbord asks about professional historians and boredom in Is Professional History Boring? and tells us about 17th century “disease mongering” in A Scurvy Epidemic in 17th-century England. […]

[…] What Europe’s Climatic Past can tell us About our Attitudes Today. The Neuromania Antidote. A Scurvy Epidemic in 17th Century England. Put Your Ethics Where Your Mouth Is (NYT competition to unearth a voice to ethical reasons to eat […]

[…] I am interested in efforts to sell medicines directly to patients, how the purveyors of those medicines identify and label symptoms in order to pathologize them, and how they use various techniques to convince audiences that they are suffering from something and should take the elixir proffered. Typically, this has been various patent medicine companies—Medicines for the Faithful and Wright’s Indian Vegetable Pills and Dr. Jayne’s Family Medicines and Quack Medical Cures and Selling Medicines in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century—though there are fascinating 17th-century parallels during a scurvy epidemic in Enland, “A Scurvy Epidemic in 17th-Century England.” […]

[…] dollar industry. In the 1670s and 1680s practitioners of all sorts promised to have a cure for the scurvy epidemic in […]

[…] A little searching on EEBO suggests that “pilulae” (and variations such as “pilula” or “pilullae”) enjoyed a heyday of marketing authority for about 20 years in 17th-century England, right around the time people seemed particularly worried about the scurvy epidemic. […]

[…] 1670s and 1680s witnessed a rapid development of a patent medicine market. See, for example, the scurvy epidemic or the Pilulae Antipudendagriae or the widespread marketing use of the […]

[…] and contemporaries understood scurvy to be and what we call scurvy are not related. Scurvy seemed epidemic in 17th-century England. […]

[…] between scurvy grass’s incorporation into the herbals in the middle of the century and the scurvy epidemic in 1670s and […]