At the end of the 18th century Thomas Scattergood spoke out against what he considered the harsh treatment people suffering from mental illness and advocated for the “humane treatment” of patients in asylums. Scattergood was an influential local Quaker who traveled extensively in the states and in England. In the early 19th century, he suggested to the Philadelphia Yearly meeting that they should do more to care for members who suffered from mental illnesses, who “may be deprived of the use of their reason.” He worked with other members of the Philadelphia Yearly meeting to establish the Friends Hospital, an asylum

for their insane brethren, which would furnish besides the requisite medical aid, such tender and sympathetic attention, and religious oversight as may sooth their agitated minds and thereby under the divine blessing, facilitate their restoration to the inestimable gift of reason.[1]

The Friends Hospital is often celebrated as the U.S.’s first mental hospital.

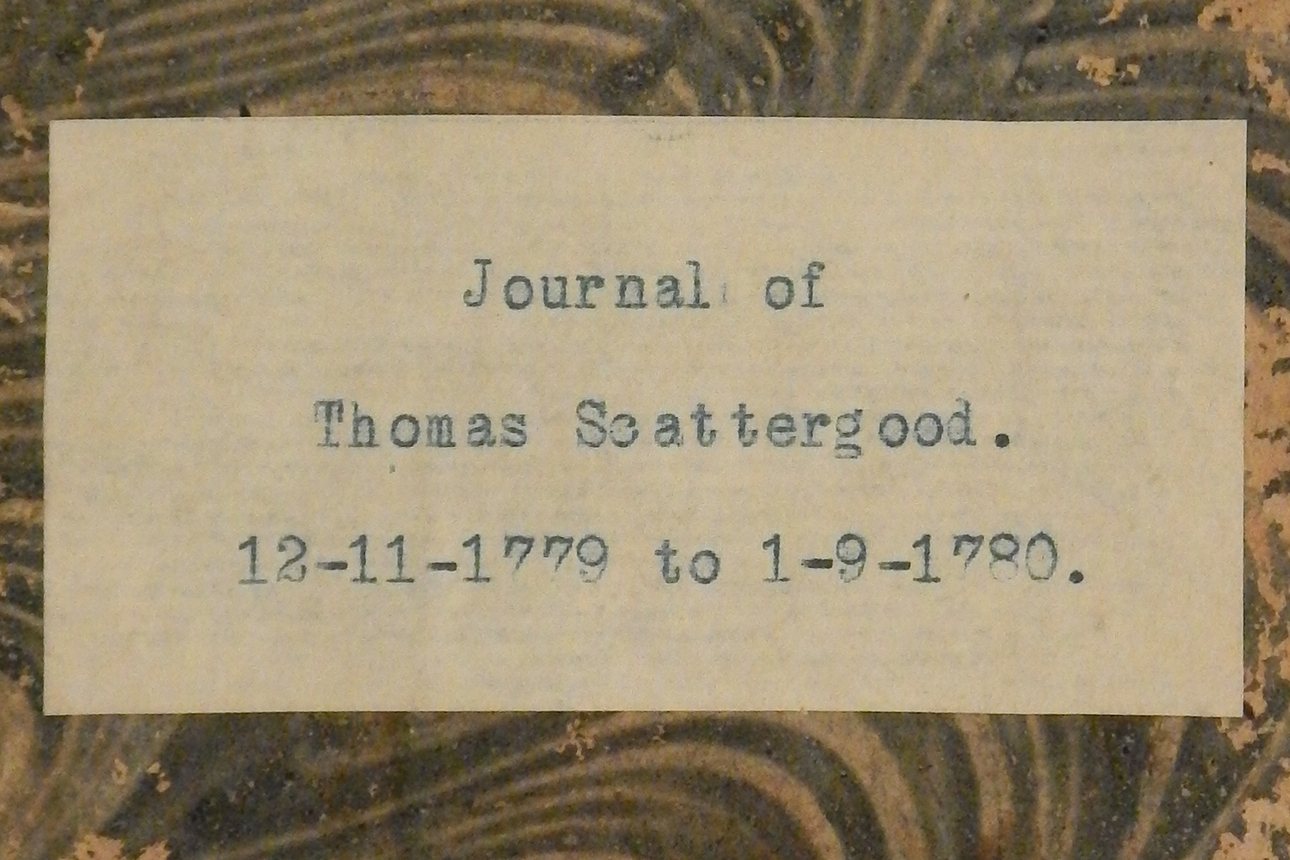

Special Collections here at Haverford College has a large collection of Scattergood Family Papers. We recently acquired 17 volumes of Scattergood’s diaries, from late 1779 to 1811.

Along with all sorts of notes about travel, daily life, and personal reflections. He also records many of his dreams—in one diary, he seems to be troubled by a recurring dream about fishing: He hooks a fish and can bring it to the wharf, but he fails to land the fish even with the help of his friends. But when the fish escapes, it never seems to swim away but lingers near the wharf as if taunting him.

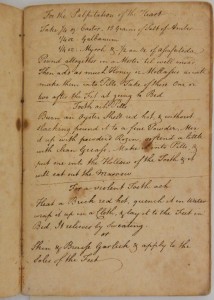

Interspersed through these diaries are various medical recipes. In his early diary, from winter 1779–80, he lists recipes for palpitation of the heart, tooth pills, and a violent tooth ache.

For the Palpitation of the Heart

Take 1/4 oz: Castor, 15 Grains of Salt of Amber 1/4 oz Galbanum 1/4 oz Myrrh & 1/2 an oz of assafectida Pound altogether in a Morter tip well mix’d Then add as much Honey or Mollasses as will make them into Pills. Take of these One or two after the Fit at going to Bed

Tooth Ach Pills

Burn an Oyster Shell red hot, & without slacking pound it to a fine Powder, Mix it up with powder’d Rozin, soften’d a little with clean Grease. Make it into Pills, & put one into the Hollow of the Tooth & it will eat out the Marrow

For a Violent Tooth Ach

Heat a Brick red hot, quench it in water wrap it up in a Cloth, & lay it to the Feet in Bed. It relieves by Sweating. or Skin & Bruise Garlick & apply to the Soles of the Feet

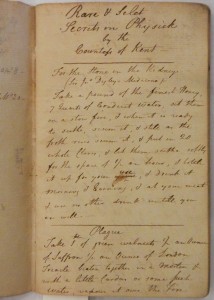

Sometimes Scattergood indicated his source. He copied a number of recipes from the “Countness of Kent” and from “Digby’s Medicine”.

His recipes range from the generic, such as those for wounds or tooth aches, to the specific. Unsurprisingly, there are a number of recipes for the plague, for “dead palsy,” and for the “Yellow Jaundice.”

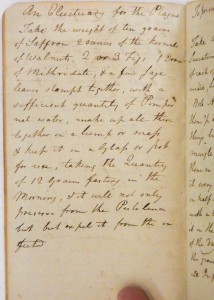

An Eluctuary for the Plague

Take the weight of ten grams of Saffron 2 ounces of the kernels of Walnuts, 2 or 3 Figs 1 Dram of Mithridate, & a few sage leaves stampt together, with a sufficient quantity of Pine kernal water, make up all these together in a lumb or mass & keep it in a glass or pot for use, taking the Quantity of 12 Grains fasting in the Morning, & it will not only preserve from the Pestilence but but expel it from the in fection

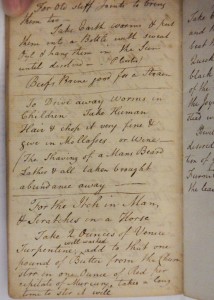

Other recipes seem to apply less to illnesses per se and more to conditions. So Scattergood records a recipe for “old stiff joints” and for childhood worms and “the itch in Man.”

To Drive away Worms in Children

Take Human Hair & chop it very fine & give in Mollasses or Wine— The shaving of a Mans Beard Lather & all taken brought abundance away—

For the Itch in Man, & Scratches in a Horse

Take 2 Ounces of Venice Turpentine well washed add to that one pound of Butter from the churn stir in one Ounce of Red per [sic] cipitate of Murcury, take a long time to stir it well

The itch in man was a type of scabs or scurvy,[2] which appeared in sheep and horses.

One way to look at Scattergood’s recipes is to see them as reflecting the diseases that worried him. If we understand that plague and pestilence did not pick out unique diseases but were rather related to epidemics of various sorts, and we recall his having lived through the Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia—at one point in a diary he laments that he has left his wife and children to suffer in a lesser epidemic (perhaps another Yellow Fever outbreak)—we can understand his interest in the many plague recipes. Generic recipes for cleaning and treating wounds shouldn’t surprise us.

Equally interesting are the ingredients Scattergood lists: butter, walnuts, mithridate, red precipitate of mercury, Venice turpentine, quick silver, saffron, oyster shells, galbanum, and asafeotida. Many of these ingredients are found in most herbals of the time. Others seem more exotic and probably harder to obtain. Others must have been purchased from apothecaries or chemists, e.g., Venice turpentine or red precipitate of mercury.

Perhaps spending more time with Scattergood’s diaries will reveal when and how he used these recipes. In any event, they offer a glimpse into late 18th-century life and medicine.

-

Scattergood has become closely associated with mental and behavioral health. See, for example, Scattergood Foundation and Scattergood Ethics. The quotation is taken from Scattergood Ethics : Thomas Scattergood. ↩

-

Clearly what Scattergood and contemporaries understood scurvy to be and what we call scurvy are not related. Scurvy seemed epidemic in 17th-century England. ↩

One reply on “Thomas Scattergood’s Medical Recipes”

[…] in Panama) and older popular treatments (as was Thomas Scattergood in the early nineteenth century, here and […]