The Shot@Life Campaign is the latest effort to vaccinate less fortunate children in developing countries. Part of the United Nations Foundation, Shot@Life hopes to expand access to vaccines by drawing on “the American public, members of Congress, and civil society partners.” While the Shot@Life seems to result from improved, modern public health, universal vaccination especially for poorer children has clear historical antecedents in 19th-century Philadelphia. Sometime around the middle of the century physicians signed a petition urging Pennsylvania’s senate and house of representatives to support “the universal extension of vaccination” against smallpox.

Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine in the late 1700s—1796 is usually cited as his first successful vaccination. Jenner’s technique was soon introduced into the Boston area. Before long Philadelphia appointed people to locate unvaccinated children so that “physicians duly appointed [could] call upon and vaccinate them free of charge.”

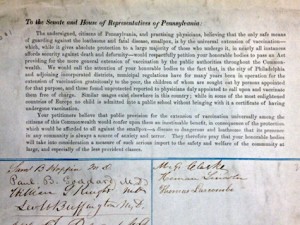

The petition is remarkable for how contemporary it sounds. It raises issues of public health and welfare, government required vaccination programs, vaccinating school children, and the real financial costs of vaccinating children. A copy of this petition signed by 20 local physicians survives in Haverford College’s Quaker & Special Collections. It would be interesting to know if other copies of this petition survive, perhaps in the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and to begin to reconstruct the history of smallpox vaccination in the Philadelphia area.

Here is the full text of the petition:

To the Senate and House of Representatives of Pennsylvania

The undersigned, citizens of Pennsylvania, and practicing physicians, believing that the only safe means of guarding agains the loathsome and fatal disease, smallpox, is by the universal extension of vaccination—which, while it gives absolute protection to a large majority of those who undergo it, in nearly all instances affords security against death and deformity—would respectfully petition your honorable bodies to pass an Act providing for the more general extension of vaccination by the public authorities throughout the Commonwealth. We would call the attention of your honorable bodies to the fact that, in the city of Philadelphia and adjoining incorporated districts, municipal regulations have for many years been in operation for the extension of vaccination gratuitously to the poor, the children of whom are sought out by persons appointed for that purpose, and those found unprotected reported to physicians duly appointed to call upon and vaccinate them free of charge. Similar usages exist elsewhere in this country; while in some of the most enlightened countries of Europe no child is admitted into a public school without bringing with it a certificate of having undergone vaccination.

Your petitioners believe that public provision for the extension of vaccination universally among the citizens of this Commonwealth would confer upon them an inestimable benefit, in consequence of the protection which would be afforded to all against the smallpox—a disease so dangerous and loathsome that its presence in any community is always a source of anxiety and terror. They therefore pray that your honorable bodies will take into consideration a measure of such serious import to the safety and welfare of the community at large, and especially to the less provident classes.

[Reposted at PACHS.]

One reply on “Universal Vaccination is a Perennial Struggle”

A neat example of the religious freight loaded onto such interference with divine providence can be found in the first inoculation controversy in New England, when Cotton Mather FRS was pitted against his fellow ministers and the anti-clerical William Douglass MD. [religious position forgotten by me]

THe dynamics of the New England debate’s religious meaning was rather different from that in England, where nonconformists and Whigs were on one side against the High Churchmen [also non-jurors] and Tories [also Jacobites] on the other. Two different views of providence.