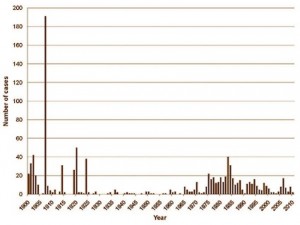

There is little new about the latest reports about a man in Bend, Oregon, suffering from Y. pestis,the dreaded Plague or the Black Death. Plague is endemic in the South West and the West, with cases reported every year since the mid-1950s (see the useful CDC page on plague distribution statistics). Four people in Oregon have suffered from the plague since 1995; this latest case will be the fifth. Today, plague is treated with antibiotics—the victim is being treated with antibiotics and his family members are receiving preventive doses.

On some level, any case of plague is cause for concern, but this single case does not seem to warrant raising alarms about a new epidemic or claiming without some qualification that “[s]ome scientists, however, are worried about a resurgence if the plague-causing bacterium develops a resistance to antibiotics, something that seems to already be happening.” This claim is based on a 2007 article at SciDev.net that, in turn, reports on an article from PLoS ONE. Citing earlier work, the PLoS ONE article points to a single case of multiple antimicrobial resistant plague isolated in Madagascar in 1995. This case displayed a “high-level resistance to antimicrobial agents,” that is, to the three drugs recommended for treating plague: streptomycin, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol. In the end, a combination of streptomycin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (often recommended for prophylactic therapy) proved effective.

In a world concerned with bioterrorism and overseen by Homeland Security, fears of an “aerosolized plague weapon” are predictable as is the “Working Group on Civilian Biodefense.” But even using plague as a weapon is not new. The Soviet Union reportedly stored what they hoped would be weapons-grade plague during the Cold War (the U.S. tried “but couldn’t get the germs to stay virulent”); the Japanese dropped plague infested fleas over China during World War II. And then there is Gabriele de Mussis’s horrific account of the Tartar armies catapulting plague victims into the Genoese city of Caffa on the Black Sea. This is 14th-century biological warfare at its most gruesome:

See how the heathen Tartar races, pouring together from all sides, suddenly invested the city of Caffa and besieged the trapped Christians there for almost three years. There, hemmed in by an immense army, they could hardly draw breath, although food could be shipped in, which offered them some hope. But behold, the whole army was affected by a disease which overran the Tartars and killed thousands upon thousands every day. It was as though arrows were raining down from heaven to strike and crush the Tartars’ arrogance. All medical advice and attention was useless; the Tartars died as soon as the signs of disease appeared on their bodies; swellings in the armpit or groin caused by coagulating humours, followed by a putrid fever.

The dying Tartars, stunned and stupefied by the immensity of the disaster brought about by the disease, and realising that they had no hope of escape, lost interest in the siege. But they ordered corpses to be placed in catapults and lobbed into the city in the hope tha the intolerable stench would kill everyone inside. What seemed like mountains of dead were thrown into the city, and the Christians could not hide or flee or escape from them, although they dumped as many of the bodies as they could in the sea. And soon the rotting corpses tainted the air and poisoned the water supply, and the stench was so overwhelming that hardly one in several thousand was in a position to flee the remains of the Tartar army. Moreover one infected man could carry the poison to others, and infect people and places with the disease by look alone. No one knew, or could discover, a means of defence.

Today, you are much more likely to contract the plague through contact with infected rodents, in other words, through your own carelessness. As Emilio DeBess, Oregon’s public health veterinarian, pointed out: “Taking a mouse out of a cat’s mouth is probably not a good idea.”

[A note on terminology: the term Black Death was coined in the early modern period, perhaps as early as the mid-16th century, but did not become widely used until the 19th century after the publication of I.F.C. Hecker’s The Black Death in the Fourteenth Century. And it is not clear that the term was meant to describe the plague’s “blackening effect on infected skin.”]

One reply on “The Plague in Oregon”

[…] Gaylord, the Oregon man who contracted the plague last month is recovering after a particularly nasty struggle with both bubonic and septicemic […]