A recent article at the BBC asks, “Why do Innocent People Confess?” For historians of witchcraft this article—the basic question, the reason prosecutors prefer confessions, and the reasons innocent people confess—will look remarkably familiar. Every time I teach my course on witchcraft students ask why anybody would confess to witchcraft. Motivated by a belief that witches never existed and witchcraft is impossible, they want to know two things: Why did innocent women and men confess to bewitching, harming, and sometimes killing other people? And why did anybody believe those confessions? The BBC article focuses on the first set of questions.

According to the BBC, Japan’s criminal conviction rate is over 99%, based largely on confessions. Those accused of committing crimes are interrogated in small, isolated rooms open only to the interrogators and the suspect. Suspects are questions night and day for hours on end. They are offered prewritten confessions to sign. They know that prosecutors are typically more lenient on those who confess. And really, all the Japanese want is “to find out the truth—exactly what happened through confession” and remain confident that “most of the confessions are truthful and they play an important part in convicting criminals.” The article suggests some psychological and cultural reasons Japanese suspects are eager to confess crimes they didn’t commit—shame being an important one.

Early modern prosecutors could hardly have said it better. They too, just wanted to learn the truth and to help convict criminals, especially witches. Innumerable manuals guide judges, inquisitors, justices of the peace, and other investigators in their search for witches. Probably the most famous is Heinrich Kramer and Johannes Sprenger’s Malleus Maleficarum, which includes a long discussion of how a suspected witch is to be interrogated and why.

Crimes of Witchcraft presented something of a challenge. Rarely were there any witnesses to the actual crime. Consequently, confession was thought to be an important tool in prosecuting suspects. Confession could be extracted through various forms of interrogation. According to certain law, confessions obtained under torture—no doubt a subjective term—had to be repeated voluntarily—again, no doubt a subjective term. The Trial of Tempel Anneke records a fascinating and haunting case that occurred in 1663 in Brunswick, Germany.

In early seventeenth-century England Richard Bernard published his A guide to grand-jury men, which guided investigators in their efforts to ascertain the truth—exactly what happened. He discusses various forms of confession, from implicit confession, the testimony of other confessed witches, to voluntary confession:

By the Witches owne confessions of giving their soules to the divell, and of the spirits which they have, and how they came by them. If any thinke that it is almost impossible to make Witches confesse thus much, they are deceived; for I find by Histories exceeding many to have confessed, and in our owne Relations of arraigned and condemned Witches, wherein I finde how a Witch hath confessed the fact, to the afflicted, being brought unto him, and charged with bewitching him: as Alizon Device did to John Law. So to the afflicted friends, as did Mother Samuel to M. Throgmorton. Some to Justices, when they were examined, as did the Lancashire and Rutland Witches. Some to the Judges so freely, as made the Judges and the Justices to admire thereat, as they did at Lancaster. Some in terrour of consciences, truely apprehending the fearefulnesse of their league made, as did on Magdalena a French Gentlewoman, seduced by Lewis Gaufredy, who also himselfe at length made a large confession before his death.

We see therefore, that Witches may be brought to confesse their Witchcraft. And thus much for the sound evidenes, more then presumptions, upon which they may bee found guilty, and iustly be condemned, and put to death

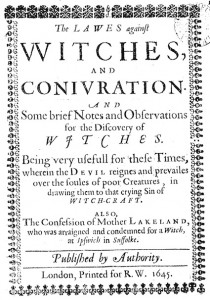

Bernard then details the many ways witches can be examined. His advice was condensed and repackaged for a more popular audience in the middle of the century in the pamphlet The Lawes against Witches and Coniuration. Here Bernard’s sometimes cautious guidelines were presented more forcefully.

When Bernard described implicit confessions, he recognized that they were problematic:

An implicit confession, when any come & accuse them, for vexing them, hurting them, or their cattell; they shall hereupon say, “You should have let me alone the:” as Anne Baker a Witch, said unto one Miles: or, “I have not hurt you yet,” ass Mother Samuel said to the Lady Cromwell, when she caused her hair to be burnt: or to say to one, “I will promise you that I will doe you no hurt,” upon this or that condition, as other have said. These kind of speeches are in manner of confession of their power of hurting, and yet but presumption; because such speeches have beene, and are used upon diverse occasions, by others which are no Witches

Two decades later, the pamphlet quoted Bernard but truncated his text after declaring “These and the like speeches are in manner of a confession of their power of hurting.” Similarly, The Lawes against Witches and Coniuration reduced Bernard’s reflections on confession to a set of operational guidelines, presented as an ordered list for demonstrating that somebody is a witch.

As if to demonstrate the utility of this list, the publisher appended to the pamphlet “The Confession of Mother Lakeland of Ipswich, who was arraigned and condemned for a Witch, and suffered death by burning, at Ipswich in Suffolk, on Tuesday the 9. of September, 1645.” Apparently Mother Lakeland confessed “The Devil came to her first between sleeping and waking, and spake to her in a hollow voyce, that if she would serve him she should want for nothing. After often sollicitation she consented to him.” The devil gave her “three Impes, two little Dogs and a Mole (as she confessed).” She bewitched her husband and tormented him, “(as she confessed) whereby he lay in great misery for a time, and at last dyed.” She confessed to sending her imps, her dogs, and her mole out to torment and harm others. While no witnesses could provide testimony to her crimes, her confession was enough to condemn her to be burnt. Two decades later, in Brunswick, Tempel Anneke confessed to fornicating with the devil and binding herself to him, but only in a granary.

Witchcraft confessions should raise various questions for us. What is the status of any confession? What makes a confession believable? Why are confessions thought to be better than other forms of evidence? Whose interests are served by privileging confessions? How do interrogation techniques such as threats, physical or psychological stress, torture, pre-written confessions, isolation, or leading questions taint a confession? As the BBC article indicates such techniques are not relegated to the past. Witchcraft confessions—the procedures that produced them, the courts that accepted and acted on them, the public that believed them, the authorities that endorsed them—should prompt us to think about the social, political, and judicial work any confession is doing.