Today’s many news reports on the meteor that crashed to earth in Russia reminds us that comets, meteors, stones falling from the sky, and other blazing stars have long fascinated people. This morning’s meteorite attracted all the more media attention because it was unexpected. In a world where all meteors and comets were unexpected, they often terrified onlookers and were always portentous.

In his Natural History Pliny reported that Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, famous for having explained eclipses, used his astronomical knowledge to predict that various stone would fall from the sun. So marvelous were these stones, Pliny reports, that “A stone is worshipped for this reason even at the present day in the exercising ground at Abydos—one of moderate size, it is true, but which the same Anaxagoras is said to have prophesied as going to fall in the middle of the country.”

Many chronicles include reports of fiery stones—typically, these are probably comets—which are then related to significant historical events. The Hartmann Schedel’s Liber chronicarum, typically referred to as the Nuremberg Chronicle, contains a number of images of comets (the BSB’s beautiful color copy is available here).

One of the more famous images comes from the Bayeux Tapestry, where we see a group of onlookers marveling at a comet streaking across the sky (typically, this is understood to be Halley’s Comet):

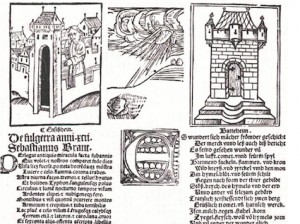

The earliest datable and surviving meteorite crashed to the ground on 7 November 1492 near Ensisheim. It immediately became a set piece in Sebastian Brant’s political rhetoric. Brant enlisted the meteor in support of Emperor Maximilian’s efforts to unite the empire under his control and interpreted it as evidence of the Emperor’s success in his struggles against the French.

In Albrecht Dürer’s famous Melancholia a comet can be seen shooting across the sky (there is a digital version of Dürer’s Melancholia at the BL).

Every time a comet appeared, astrologers and other experts rushed to compose texts that promised to reveal what the comet meant. In 1468 and again in 1472 the Polish astrologer Martin Bylica along with numerous other astrologers across Europe wrote judicia that they dedicated to local princes and kings. Bylica dedicated his to the Hungarian king, Matthias Corvinus, and ensured him both times that these comets augured well for his military struggles with, first, the Bohemians and, second, the Austrians. Comets and other portentous phenomena graced the title pages of numerous pamphlets. Again, many of these are comets rather than meteors. In some cases, it is difficult to know what the author witnessed. Johannes Virdung’s Ußlegung und erclerung der wunderbarlichen kunftigen erschrocklichen ding … den mann Comet nent (from the copy at the BSB) is a typical example of this.

In every case, these celestial phenomena were analyzed to reveal either their role in shaping history, in the case of the chronicles, or for their influence on contemporary society, in the case of Brant and many of the pamphlets in the sixteenth century. Celestial phenomena were always overflowing with meaning and significance. While we draw different meaning from today’s meteor, we are no less interested in it.

While we probably should take Elly’s suggestion and forge a sword, we would be arriving late to the swords-forged-from-meteors party. Not only is King Arthur’s Excalibur purportedly forged from a meteor (for example, in Marion Zimmerman Bradly’s The Sword of Avalon), Marvel Comic’s Ebony Blade was carved from a meteor for the Black Knight. And then, more recently, Harvey Abramowitz, an engineering professor from Purdue University Calumet, apparently forged his own sword from a meteorite.

Update: Go read Medieval Robots’ post and learn about Terry Pratchett’s meteorite sword.

One reply on “Meteorites and Comets in Pre-Modern Europe”

[…] For other recent blogging on historical comets, see Darin Hayton on “Meteorites and Comets in Pre-Modern Europe” and Rupert Baker on the comets in the Philosophical Transactions (“Watch the […]